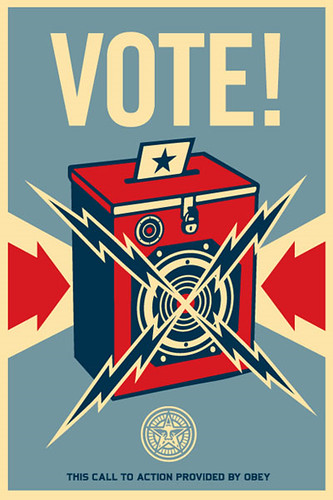

I'm on pins and needles, people. Have bitten my nails into the quick. Stomach in knots big enough to anchor a billionaire's yacht. Election Day is almost here, but instead of pumping up the volume on CNN and turning my living room into campaign headquarters, I think it may be best for me to focus on something else right now, to go to my happy place. Yes, it's I Spy Art Day here at Design Crisis, where I bring you a roundup of interior design's latest muse. Today's special is the always interesting photographer, Adam Fuss.

Adam Fuss is one of those old school dudes that I can identify with. Instead of embracing the novelty of digital wizardry, Fuss goes back to basics by frequently ditching the camera altogether and dealing with the light sensitive properties of photographic paper itself. In the home of Pieter Estersohn, seen in New York Social Diary, this photogram of Estersohn's son Elio hangs as a super realistic, one of a kind baby portrait. Instead of capturing a representation of the baby, Adam Fuss captures the shadow of the baby crawling over the paper, and in a sense, he captures the baby itself (but not literally, because that would be illegal).

While Estersohn was lucky enough to have a portrait made for him, most of the pictures floating around the designosphere are of Fuss' black and white photograms of smoke.

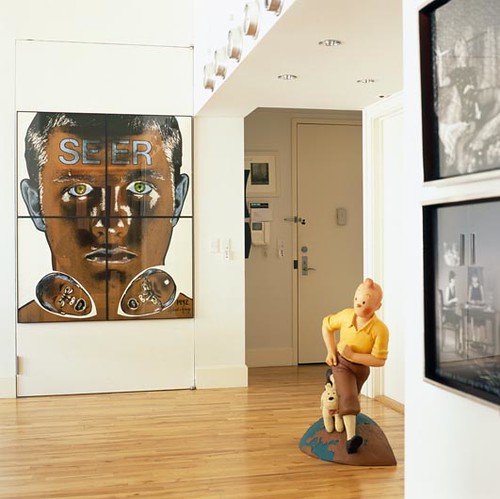

Donald and Phillip's amazing art filled home in San Francisco features this small Fuss photogram (courtesy of More Ways to Waste Time).

Generally, Fuss' pieces tend to be large in scale, so that they become a viewing experience where one is enveloped in the image, as seen in this gorgeous Paris apartment.

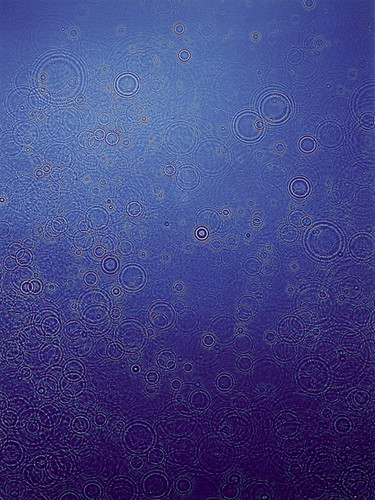

To stand in front of one of Fuss' photograms of smoke is to stand in a whirling maelstrom of eddies and currents. Sounds like my stomach. So much for happy distractions!

All of Fuss' work is intensely aesthetic, seductive in both its delicacy and first generation sharpness. The print over the fireplace makes a lovely addition to this Smoke and Mirrors themed room designed by Steven Volpe featured in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Earlier works involved hanging bare bulbs on a string and allowing them to move, exposing the paper in a pattern of spirals, as seen in this home of Charles Allen, featured in Architectural Digest.

Fuss' black and white works may be particularly popular in the design world because they behave so minimally on the wall, as seen in this apartment featured on Habitually Chic.

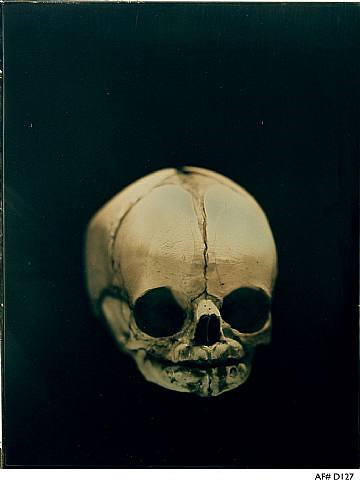

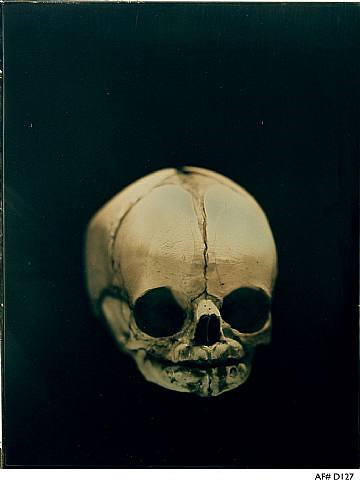

It's like very elegant (and expensive) white noise. But I have followed Fuss' work for years, and he certainly didn't start out as a decorator's favorite. Many of his earlier works recalled death and decay, and a very studied interest in photography's unique ability to capture the "what has been," as philosopher Roland Barthes said.

These beautiful plants were pressed onto paper, exposed with light, and captured with a permanence that a real pressed flower can never emulate. It's the intersection of mortality and immortality, and it gets back to the basics of what photography initially set out to do: to preserve a slice of time.

This exact configuration of smoke only existed for the split second that it was illuminated by light. And then it was gone.

The images in his My Ghost series reference the impermanence of time and, consequentially, of life. A child could fit into this christening dress for a matter of weeks, perhaps, before she/he outgrew it. As the Greek philiosopher Heraclitus said, "Panta Rhei." Everything changes. You cannot step into the same river twice.

And raindrops will never fall in this same pattern again.

Recently, Fuss has begun experimenting with other forms of image making, taking up the Daguerreotype (at which time he became my hero, since I used to make them, too) as another way to create one of a kind images. The Daguerreotype was the Victorian's medium of choice, and its clarity was shocking to them (and still is - the sharpness of digital isn't even close).

The Victorians famously used Daguerreotypes to record (in addition to more conventional portraits) images of their deceased children, posed as if sleeping. Perhaps they were creating an alternate universe where the child might have lived. Or perhaps the images acted as reminders that nothing lasts forever. Fuss has a similar predilection for Memento Mori and its imperative to seize the day.

Once again changing his method of production, Fuss photographed butterfly chrysalis and enlarged them to six feet tall for his latest series.

As iconic symbols of transformation and metamorphosis, they are compelling both in their stasis and potential energy.

Fuss' photographs act as talismans, reminders of the past and its contrast to the present. And so they are also avatars of change. Nothing can stay the same.

Nor should it.

(Art images courtesy of the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, Art Lies, Artnet, and Photography Now.)